How to analyze situations = systems

Key message: The goal of an analysis is to draw conclusions. We understand a situation = a system when we can explain how all elements work together to form "the whole".

Unfortunately, the text is a bit complicated because many things have to be considered when analyzing complex situations.

What are situations? What are systems?

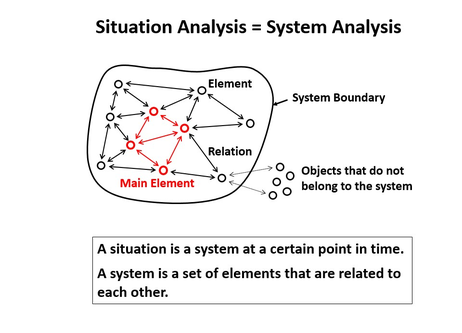

A situation describes the relations between several elements (persons or things) at a point in time. (I cannot imagine a situation that consists of only one element.) So a situation is a system at a certain point in time. When I analyze a situation, it means that I am analyzing a system.

Definition: A situation is a

system at a certain point in time.

Definition: A system is a set of interrelated elements. The viewer can decide where to place the system boundary, but the boundary should make sense.

What is an analysis?

"An analysis ... is a systematic investigation in which the examined object is broken down into its components (elements). These elements are identified on the basis of criteria and then ordered, examined and evaluated. In particular, one looks at relationships and effects ... between the elements. The opposite term to analysis ('breaking down into individual components') is synthesis ('putting elements together to form a system')." (https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Analyse, 24.11.21)

An AI says: A systematic investigation is a planned, methodical, and comprehensible approach. In my opinion, an investigation is systematic if it takes into account all elements of the system under investigation.

"As analysis is conceived to be a sort of picking to pieces, so synthesis is thought to be a sort of physical piecing together ... In fact, synthesis takes place wherever we grasp the bearing of facts on a conclusion ..." (John Dewey (1910). How We Think. Boston: D. C. Heath & Co., p. 114)

Since the term "synthesis" is not very well known in the context of an analysis, I have omitted it from the title of this text. Nobody performs an analysis without conclusions. The conclusions can be considered as a part of the analysis or they can be called synthesis on their own.

So there are 2 definitions of analysis:

1. An analysis is an investigation that collects information about the behavior of the object as a whole and, after the object has been broken down into its components, about the properties of the components and their relationships to one another. Then conclusions are drawn that explain the behavior of the object.

2. An analysis is an investigation in which information is gathered about the behavior of the object as a whole and, after the object has been broken down into its components, about the properties of the components and their relationships to each other. The subsequent drawing of conclusions that explain the behavior of the object is called synthesis.

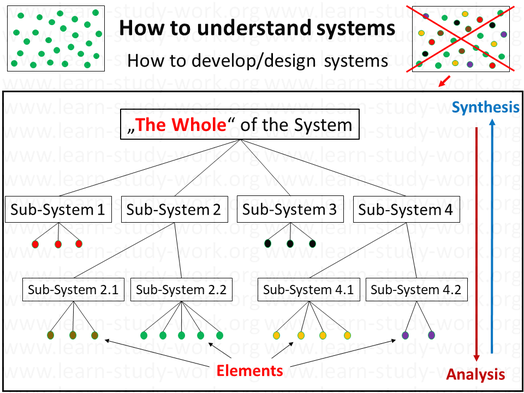

People say: The "whole" (of a system) is more than the sum of its parts. A system therefore consists of at least two levels: the level of the whole and the level of the parts.

"... we observe that the concept always distinguishes between (at least) two different levels of abstraction, or systems levels: the system as a functioning unit and the system as a set of interacting parts." (www.swemorph.com/pdf/anaeng-r.pdf, 26.02.20, p. 6)

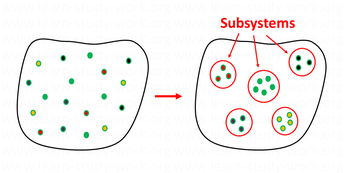

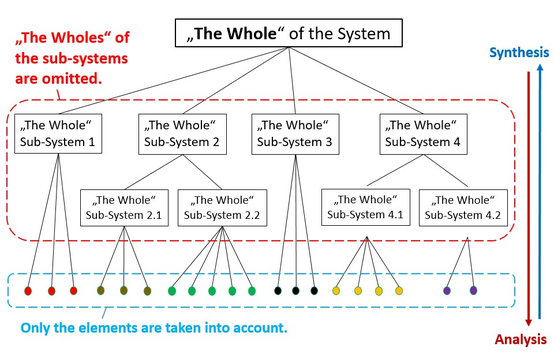

The level of parts often has several sub-levels

because many systems include sub-systems (see the images below).

The "whole" is the behavior (functioning) of the whole system that results from the interaction between its parts. Different behaviors may be important to different observers of a system.

Therefore, the "whole" of a system always depends on the viewpoint of the observer.

The observer has understood the "whole" of a system when he can explain and predict the behavior of the system with regard to the application that interests him. In other words, if you understand the "whole" of a system, you can influence and use the system as you need it.

What are the three steps of an analysis?

No matter which definition one prefers, the three steps of an analysis or analysis/synthesis are the same. However, it is possible to swap steps 1 and 2. In this case, the behavior of an object is first examined as a whole, i.e. as a black box, and only then is it broken down into its components in order to explain its behavior as a whole (see under step 2). This is advantageous when you want to analyze a particular behavior or property of the object.

Step 1: The object is divided into its components (elements) and these are ordered.

Three cups on a table are a simple example of a system. Simple systems, unlike complex systems, need little or no ordering.

Complex systems have many elements and there are many relationships between the elements. In addition, complex systems can be opaque (lack some information about the system) and dynamic (the

system changes over time). Complex systems are much more difficult to understand than simple systems.

If we decompose a complex system into its individual elements, we get a large number of elements. Therefore, it is useful to arrange (categorize) the elements into groups. The groups can be

considered as subsystems of the whole system.

Continuing this approach leads to a hierarchical representation that shows the structure of the system. (The structure of a system is the arrangement of its elements.) It is only when all elements are equal that they cannot be categorized into subsystems.

The figure above shows the hierarchical structure of a complex system (the structure of a system is the arrangement of its elements). The figure gives us an overview of the system elements and also a first indication of their relationship to each other, because we can see which elements belong together.

Example: Non-fiction books are systems of statements and their table of contents shows the hierarchical arrangement of these statements. Therefore the table of contents of a non-fiction book is an example for the figure above.

"Only the knowledge of the elements and their structural arrangement enables understanding of systems and explains the statement that the whole is more than the sum of the parts." (Daenzer, W. F. (1976). Systems Engineering: Leitfaden zur methodischen Durchführung umfangreicher Planungsvorhaben. Peter Hanstein Verlag, Köln, p. 12)

Step 2: The behavior of the object as a whole, its components (elements) and their relationships to each other are examined.

When we say, "I want to analyze this system (situation)," we mean, "I want to understand this system (situation)." So, we have to collect so much knowledge about the system during the investigation that we can draw conclusions in the 3rd step. We obtain the knowledge we need for this through observation (questioning), experimentation, reading professional literature, asking experts, or using creativity techniques.

The investigation of a system can begin with an examination of the "whole" as a functioning unit (black box analysis) or with an examination of its parts (its elements).

"We regard a system as a primary unit [a functioning unit] when we treat it as a black box and ask about its overall behavior - i.e. what it does or accomplishes. For example, we may submit our

black box to various inputs and observe the resulting outputs.

As a set of parts or components (which somehow work together to produce the system's overall behavior) we can examine the system's construction - i.e. its internal structure and processes. ...

and the specific relationships between its parts ...

... the choice of a suitable method for the study of a given system depends, to a large extent, on the type of knowledge that is empirically accessicble to us ..." (www.swemorph.com/pdf/anaeng-r.pdf , 26.02.20, p. 6-7)

Whether you start with a functional analysis (black box analysis) or a structural analysis can vary, for example when designing products or processes:

"Often the structure has not yet been determined in the early concept phase. However, the functions are already clear ... If, however, an adaptation is required instead of a new development, it is (usually) easier to do the structural analysis before the functional analysis." (Werdich, M. (2011). FMEA – Einführung und Moderation. Vieweg+Teubner Verlag/Springer, p. 19)

Sometimes it makes sense to start with both approaches at the same time: When the police are looking for a serial killer, they examine all the evidence (the elements) and at the same time a profiler describes the criminal profile of the killer ("the whole"). If later both fit together, then the perpetrator has been found.

Some psychologists do situation research because they want to predict the behavior of a person in a special situation:

"... considering the situation the person is currently in can enhance behavioral prediction. ...

Elements that are physically present and constitute the situation [the important elements] are referred to as situation cues ... Cues give the answer to five simple W-questions. Who is with you? Which objects are around you? What is happening? Where are you? When is this happening? ... Listing and quantifying all cues ... in a situation would take a tremendous amount of time and effort, if it could even be achieved.

... assessing situations via their perceived characteristics requires that perceivers rate situations on these characteristics. ... For example, most people would agree that sitting in a café and enjoying a drink with friends is more pleasant than cleaning one’s house. Of course, some people may hold a different view on this, which needs to be explicitly considered when seeking to assess the situation in its completeness." (Horstmann, K. T., Rauthmann, J. F., & Sherman, R. A. (2017). The measurement of situational influences. In V. Zeigler-Hill and T. K. Shackelford (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Personality and Individual Differences, page 2-9)

This means: To understand a situation, we must first identify the main elements/the important sub-systems, because it would take too much time to examine all the elements, even the insignificant ones (see the images above). The main elements/sub-systems have characteristics (properties) and rules apply to the relationships between them. We must examine these characteristics and rules.

To do this, we need imagination because we have to put ourselves in the position of a main element/sub-system and ask ourselves: What are my characteristics? How do I influence the other elements of the situation? What rules apply to me? How have I developed over time? How will I behave in the future?

"The toddler plays different roles, imagining himself to be a mother, a doctor, a pilot ... 'Ordinary' people are creative when they ... mentally play through possible courses of action ..." (Winter, H. (2016). Entdeckendes Lernen im Mathematikunterricht. Braunschweig: Vieweg, S. 218)

Step 3: Conclusions are drawn that consider the object as a "whole" and take into account all the results of the investigations.

When we recognize the rules and facts that apply to a system as a black box and to the relationships between the parts of the system, we can infer "the whole" and fully explain the behavior of the system.

A complex system is "made up of a large number of parts that interact in a non-simple way. In such systems, the whole is more than the sum of the parts ... in the important pragmatic sense that, given the properties of the parts and the laws of their interaction, it is not a trivial matter to infer the properties of the whole." (Simon, H. A. (1962) The architecture of complexity. Proc. Amer. Philos. Soc. 106(6) 467–482)

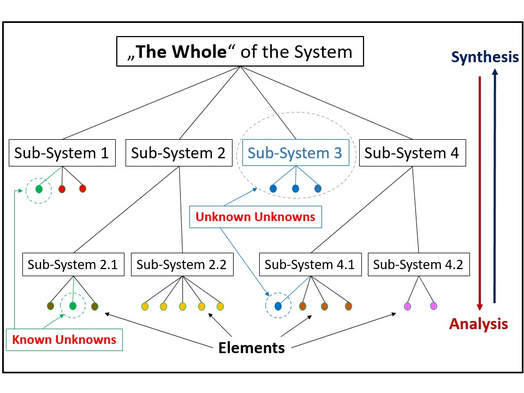

Often the information about a system is not complete. For some elements of a system, we know that our information is insufficient. These are known unknowns. But there are also elements and properties that we even don't know that they exist. These are "unknown unknowns" whose possible existence we can only imagine with imagination and a sense of possibility (see below).

"In February 2002, Donald Rumsfeld, ... stated at a Defence Department briefing:'There are known knowns. There are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we now know we don't know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we do not know we don't know.' ..." (Logan, D. C. (2009). Known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns and the propagation of scientific enquiry. Journal of experimental botany, 60(3), 712-714.)

If we cannot synthesize the "whole", then we need more information about the system/situation and need to analyze further. We carry out the analysis and synthesis alternately until we are satisfied with our synthesis or no new insights are possible through further analysis. Even if we don't have enough information, we can come to conclusions that aren't substantiated.

Synthesizing a "whole" is like putting a puzzle together. If each piece of the puzzle is placed in the right place, then it is possible to see the "whole picture". When puzzle pieces are missing, a sense of possibility is required (see below) to envision possible "whole pictures". From these alternatives, we select "the whole" that best fits our research results and best explains our system/situation from our point of view.

If our idea of the "whole" suddenly becomes very clear, then there is a high probability that we have recognized "the whole" correctly.

However, it is also possible that we already know the "whole" and we want to understand or change the properties and effects of an element through the analysis, see the example above on the design of products/processes.

What is "the whole" of a system?

"The whole is more than the sum of its parts." So what is "the whole"?

The "whole" of a system is the most important aspect of the system for the observer. Since a system can be viewed from different perspectives (with different interests), its "whole" depends on the observer.

"Mary Midgley's quote, 'Whether something is a whole always depends on the point of view from which you look at it', suggests that the perception of a complete entity is subjective and dependent on the observer's perspective and context." (Google AI Mode, 10/23/2025)

If we put all the parts of a car in a box, then we have a sum of its parts. If we assemble all of these parts,

we have a functional unit (the car) as "the whole".

The main question to the system is here: "Can I use

it as means of transport?" As means of transport the parts in the box are useless.

Here are some examples for "the whole":

- "The whole" as knowledge/conclusion: "The whole" is the conclusion which is drawn from the examination of a system. The police analyze a crime because they want to know the offender. Another police department analyses the same crime from a different angle because they want to know how such crimes can be prevented.

- "The Whole" as a function: A customer says to a product developer: "Please develop me a product with these main functions."

- "The whole" as a key message: Every text has a key message (literature often has a moral.)

-

"The whole" as the main characteristic: Two people talk about a car. The first says, "This is a nice car." The other says, "This car uses a lot of

gas." They look at the car from different angles.

- "The whole" as the main rule: You organize a meeting. The last meeting was very controversial. For the coming meeting you set the rule: everyone respects the other's point of view.

- "The whole" as an idea: A scientist sees that many people have the same problem. He has an idea to solve this problem and starts a research project.

Only those who have carried out a correct analysis can properly recognize the "whole".

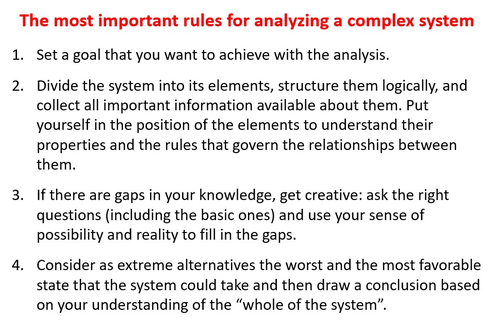

What are the rules for carrying out a analysis?

If we do not take the following rules into account, our analysis will probably be incorrect.

1. Rules for decomposing and ordering a system and for examining the elements and their relationships to each other

The first and second steps of an analysis (decomposing and examining) belong together. With a complex system, we do not have a clear idea of its structure at the beginning of the analysis. Only by examining the elements and their relationships to each other can we complete our idea of the structure of the system.

When breaking down a system into its elements, no elements should be overlooked. This is easy to say, but in complex systems there are hidden elements that are difficult to identify. That's why we need a sense of possibility:

"Reasoning denotes acute and exact mentalizing involving logical deductions. Such deductions are usually based on evidence and counterevidence. ... Rather, thinking asks us to imagine reality ... A sense of possibility does not aim for the moon but imagines something that might be possible but has not been considered possible or even potentially possible so far. ... It is necessary to constantly switch between our sense of possibility and our sense of reality, that is, to switch between thinking and reasoning. ... a sense of possibility – the ability to divine and construe an unknown reality – is at least as important as logical reasoning skills." (Dörner, D., & Funke, J. (2017). Complex problem solving: What it is and what it is not. Frontiers in Psychology, 8,1153, p. 7, www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01153/full, 17.05.24)

The sense of possibility can also be referred to as "thinking in alternatives":

"Basic principle of

'thinking in alternatives'

(Daenzer et al. 2002)

Basically, when developing solution ideas for a problem, alternatives should be considered. Developers should always check whether other solutions could be considered than the first one that

comes to mind." (Lindemann, U. (2009). Methodische Entwicklung technischer Produkte. Heidelberg: Springer, p. 46)

We cannot analyse all conceivable states of a system, but we must imagine the worst and best conceivable state of a system, i.e. we must ask ourselves: ‘How could the system get into a state that is very negative or very positive for us?’ Then we have the chance to recognise which elements could be responsible for this and how we need to influence these elements.

"Smart mathematicians are not ashamed to think small, because general patterns are easier to perceive when the extreme cases are well understood (even when they are trivial)." (Graham, R. L., Knuth, D. E., Patashnik, O. (1884). Concrete Mathematics: A Foundation for Computer Science. Addison-Wesley, p.2)

In a SWOT analysis, risks are listed, but it is important to identify the condition or conditions that must under no circumstances occur.

"The threat of a problem determines the setting of priorities. Every pilot knows the saying that has accompanied him since the beginning of his career: 'First fly the aircraft!'. As obvious as this statement may be, it is incomprehensible that it is repeatedly violated. If several problems arise at the same time, no matter how good a solution to a minor problem may be, it will not defuse the overall situation if a more important or more urgent problem has been ignored." (Bühler, J., Ebermann, HJ., Hamm, F., Reuter-Leahr, D. (2011). Entscheidungsfindung. In: Scheiderer, J., Ebermann, HJ. (eds) Human Factors im Cockpit. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, p. 162)

We also need a sense of possibility when examining the elements, because the question arises: "Are there other important properties and other important rules that we have not yet recognized?". In order to answer this question, it is very advantageous to visualize the system to be analyzed.

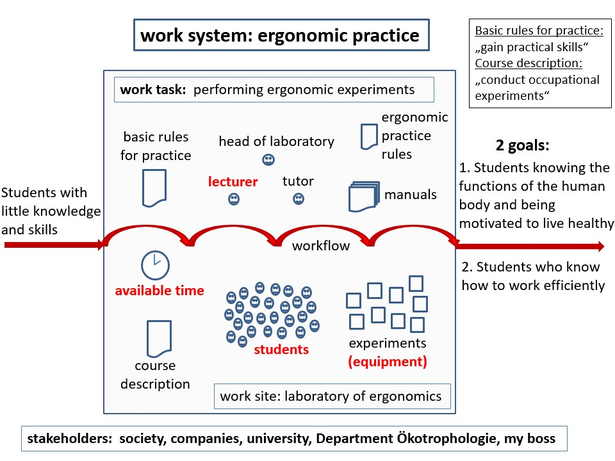

The following picture shows the representation of a work system. In the ergonomics lab course that I supervised for 18 years, two questions arose: "What is the goal of the lab course?" and "How can this goal be achieved?"

During the course of the investigation, there comes a time when the information collected is sufficient to draw conclusions or a continuation no longer promises any new findings. At this point, we should end the investigation.

2. Rules for drawing conclusions (the synthesis)

We need to understand "a thing, an event or a situation" in order to be able to infer the correct key message.

"To grasp the meaning of a thing, an event, or a situation is to see it in its relations to other things: to see how it operates or functions, what consequences follow from it, what causes it, what uses it can be put to." (Dewey, J. (1933). How We Think: restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston, D.C. Heath and Co., p. 137)

Arguments are intended to justify a conclusion.

"Arguments consist of premises and a conclusion, whereby the premises are typically intended to justify the conclusion." (https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argument und https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schlussfolgerung, 08.04.23).

If we have broken down "a thing, an event or a situation" into its components and collected a lot of information about these components and their relationships with each other, then this information is the premises ('truthable statements') on which we want to base our conclusion. Of course, we hope that our information is correct and corresponds to the truth.

Drawing a conclusion is done in two steps:

1. We decide which of the collected information is important and put it into a clear hierarchical order, as described above. It is much easier to draw a logical conclusion from logically arranged information than from disorganized information.

2. Draw the conclusion.

Before we draw a conclusion, we consider the following:

Our conclusion must take into account that "the whole is more than the sum of its parts". "The whole" is the "most important of the important". However, "the whole thing" (the conclusion) depends on what we want (depends on the "perspective" we look at the matter).

Does the conclusion refer to "how a thing operates or functions, what consequences follow from it, what causes it, what uses it can be put to?" For each question, the conclusion is different. If we are lucky, the "most important of the important" is one piece of information on our list of important information. However, we will probably have to combine several of the important pieces of information and formulate a conclusion.

The greatest danger for conclusions is that "the wish becomes the father of the thought".

"Researchers have shown that not only experience and relevant information play a role in making judgments, but also wishful thinking." (www.derstandard.de/story/2000089227452/urteile-faellen-der-wunsch-ist-der-vater-des-gedankens, 03.04.22)

"Incorrect measurement results often arise because the experimenter extracts the result he wants from insufficient data: 'The wish is the father of the thought'." (www.physik.hu-berlin.de/en/qom/lehre/ss16-physik-ii/fehleranalyse.pdf, 03.04.22, p. 10)

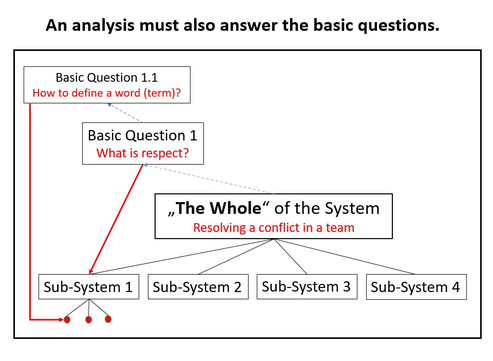

In order to gain an understanding of the "whole" of a system, we have to move upwards step by step from the lowest system level during synthesis. This means that we must also synthesize the "whole" of the subsystems. In doing so, fundamental/general questions take the place of subsystems (a "whole" always has a general and a particular side, see above).

Furthermore, we must consider:

The image shows an example in which a conflict in a team is to be analyzed. In order to understand the conflict, it is necessary to be able to answer the question “What is respect?”. In order to be able to define the word “respect”, it is necessary to know how terms are defined. The question “What is respect?” is the first subsystem of the system “Resolving a conflict in a team”.

Many people find it too laborious to synthesize the "whole" of the subsystems. They only consider the knowledge they have gained about the elements at the lowest level. Therefore, their understanding of the "whole" is limited and they only come to "limited" conclusions.

"Two things are needed to make progress: tireless perseverance and the willingness to throw away something you have invested a lot of time and effort in." (Albert Einstein)

"Persons with very high scores on the Conscientiousness scale ... strive for accuracy and perfection in their tasks, and deliberate carefully when making decisions." (https://hexaco.org/scaledescriptions, 07.02.22)

3. Summary of the rules

Continue with the other texts of the problem-solving process: "How to solve problems", "How to recognize problems", "Set goals and requirements", "How to be creative"

Read on Learn-Study-Work:

"How to define words", "What is Respect", "How to respond to disrespect", "What is Science", "What is Health", "How to write a text", "How to learn", "How to study"

en français: "Qu'est-ce que le respect ?", "Comment réagir à un comportement irrespectueux ?", "Comment écrire un texte ?"

en español: "¿Qué es el respeto?", "¿Como responder a la falta de respeto?"

in italiano: "Cosa è il rispetto?", "Come reagire alla mancanza di rispetto?"

हिंदी भाषा में: "आदर क्या है ?"

बंगाली बंगाली में: "সম্মান কি ?"